Part of a Zoom Seminar, Thursday, March 27, 2025: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/rubel-seminar-finding-a-focus-to-bread-culture-in-two-neolithic-breads-tickets-1260147578329?aff=oddtdtcreator

Note: I will be re-testing this weekend – March 22 & 23 updating as tests suggest modifying the aproaches outlined here. Wm.

These two breads were descried by Andreas Heiss in his paper on two breads found at the Parkhaus Opéra, Zurich, Switzerland, Late Neolithic lake community. The full paper is found, below. Heiss is without question one of the most important archeobotanists to work on ancient breads. His work is in the tradition Max Währen, the pioneer in bread archeology in that he looks out for bread-like starch remains in archeological settings and does his best to describe them. Heiss works today. His work is meticulous in ways that Währen’s is not. Heiss sticks to the facts, and doesn’t romanticize is finds. Romanticizing is our job.

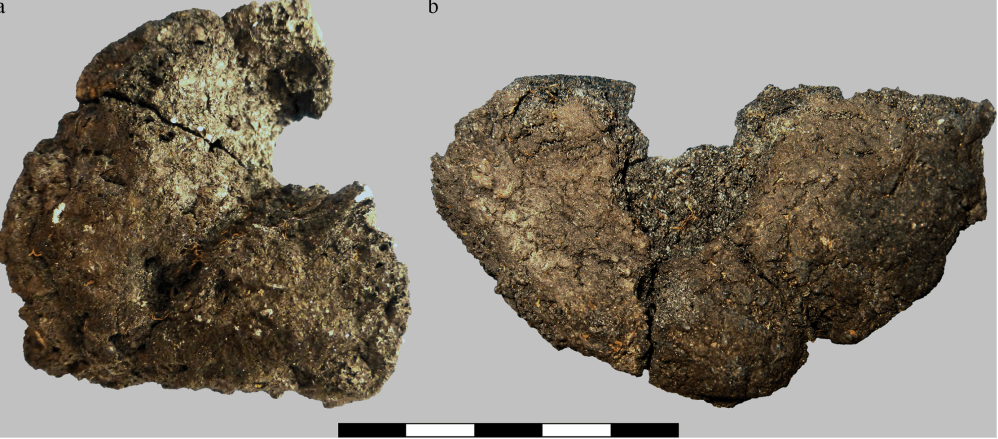

There are two breads. On the left, specimen 2285 is made of barely. The specimen on the right, 2907 is a mix of barely, emmer, and wild celery seeds.

Barley is a lower status crop. Barley fields were not fertilized, while wheat fields were. While both breads have been sifted, the barley bread is a less refined blend. 35% of that bread is made of grist larger than 1mm, while 43% of the wheat bread is made of white flour.

The wheat bread also contains wild celery seeds. These were imported from Italy, probably as part of the salt trade. Adding an expensive ingredient to the bread insures that it was understood as a luxury bread of some kind, a super luxury bread, perhaps an analogue today would be a bread with truffles.

Both breads have holes in the center. The barley bread’s hole goes all the way through while the wheat bread’s center is cleanly stamped with a disk shape — note the sharp edges. The barley bread is more crudely made than the wheat bread — we can say that less care went into the flour (less refined), that the shape is not symmetrical. The bread is lumpy. In contrast, the wheat bread is well crafted. It is symmetrical and note the precision of the center stamp.

I am sure that grinding the grain on a grindstone would help us understand these breads better than we can with modern mills. Nonetheless, Heiss gives us enough details for us to work up credible breads that we can use to ask questions that are central to the history of bread.

Recipe for Barley Bread

100% flour

50% begin around 50%. The dough stiffens when it rests. Modern recipes usually call for 70% water for barley breads, but this flour formulation is unique, so keep the illustration in mind and follow your instincts.

Barley breads smell sweet and taste delicious. They are low status breads, as they were in this ancient Swiss village. That doesn’t mean they weren’t good food. But it does mean that they may not have been given the love and care that breads made from more esteemed grains were made from. We know barley was not an esteemed grain culturally speaking because wheat was fertilized, but never barley. We have no idea what these small breads were for. The only thing we can rule out based on Heiss’ analysis is that the barley wasn’t malted. These breads were baked to be eaten.

Dough weight: Working from Heiss measurements, the dough weighed around 60 g. These are very small breads.

Shape: Try to recreate the photograph. The forming is crude. Not symmetrical. I suggest shaping a ball of dough around a stick. That is my interpretation. Why one would do this I have no idea. But this is what I think is most likely looking at the shape. It reminds me of Egyptian breads at the Egyptian museum in Turin that are clearly formed around a stick.

Flour: Barely meal. If you can buy barley with its bran intact, use that. Pearled barley, which is often the most common bulk barley, has had its bran removed. Start with what you have, working into perfection as one can.

Hydration: Hydration is always the key to bread. Writing in the 1650s, the great French author, Nicolas de Bonnefons recommends this baking off a small bit — he used a walnut sized piece of dough — as the way to know whether you need last minute recipe adjustments. Start with a 70% hydration. Let the batter sit for 30 minutes before forming into a loaf and testing by baking a small piece.

Forming the bread: The dimensions of the find are 60 mm in diameter and 20 mm high. Weigh out a 60g piece of dough and then crudely form around a stick. As one sees from the photo, do not be too careful. Not a perfect circle. The center point is not in the center.

Baking: In the end, baking is baking so we will not consider how these breads were baked. Bake in an oven at a moderate temperature until done.

Celery Seed Bread Made of Common Bread Wheat, and Emmer.

100% Mix of emmer and common wheat, red or white

50% – 60% water at your discretion.

.5 % salt (Guess based on the association of the celery seeds with the salt trade)

Celery seeds at your discretion, domestic, of course, and wild if available.

This is a luxury bread. By definition. It contains rare seeds – wild celery seeds imported from Italy — like our truffle oil! It is also made from wheat. We know from other evidence that wheat was fertilized while barley wasn’t. This loaf was made with both common bread wheat and with emmer. Sometimes, only the common bread wheat was fertilized. The bread also contains wild celery seeds from Italy. It is surmised that a salt trader returned from Italy with salt and celery sees — a light luxury product. Heiss points out that he could not tell whether salt was in the loaves. I’d surmise that the Saltzman provided salt for the bread, along with the seeds.

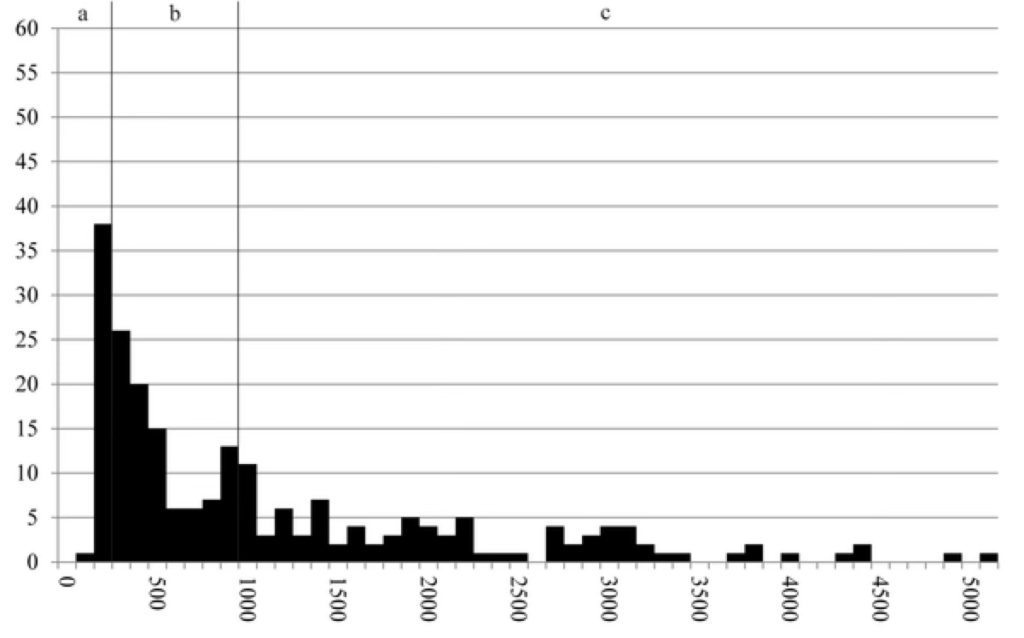

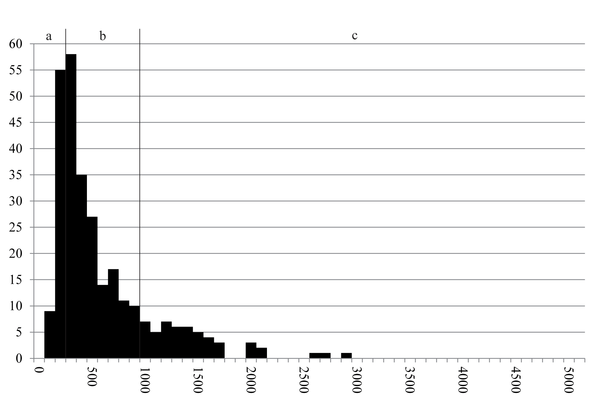

The particle size analysis shows the distribution of wheat particle sizes. If you mill your own flour, you can replicate the size distributions and the texture. Keeping in mind that this will not have been a standardized recipe — impossible before writing and mass communication — you will have to do what you can. Ratio of common wheat flour to emmer is not known. At the least, if you can’t mill your own, try to find emmer (farro) to use.

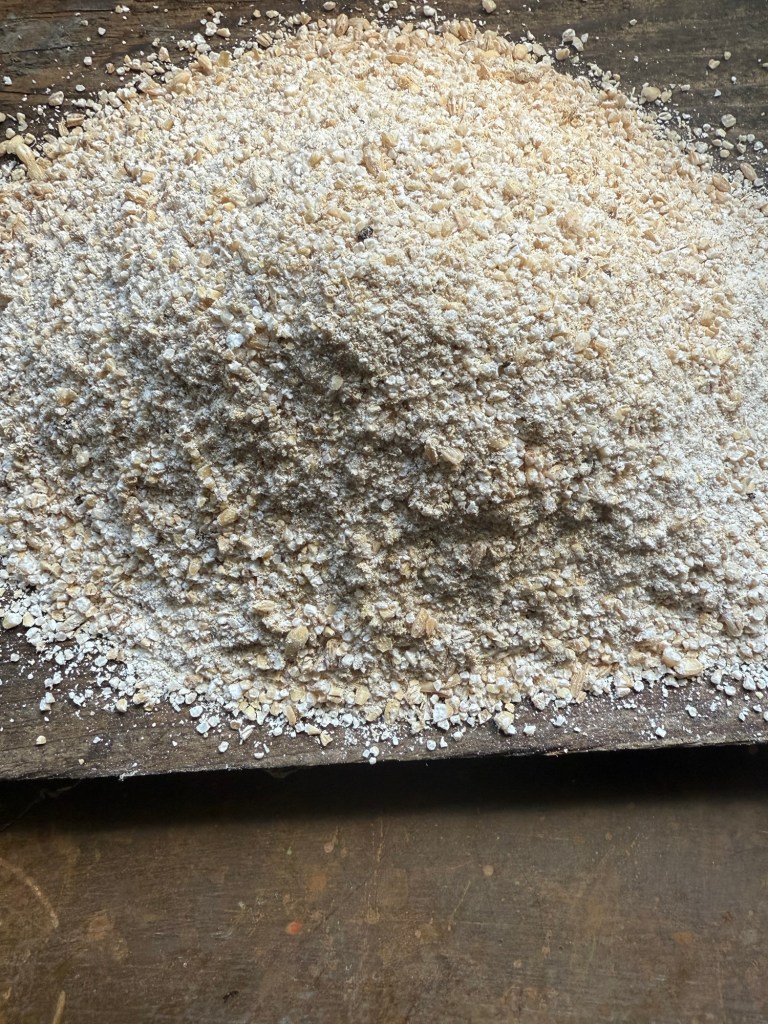

Flour. The excavated bread is an unknown mix of emmer and common bread wheat. This bread is much whiter than the barley bread. 43% of the particles are less than 300 µm. This is effectively white flour. If you don’t have a flour mill, then use white flour for this 43% fraction, and mill the rest in spinning blade coffee mill. Semolina ranging from 300 µm to 1000 µm is 24%, and grist larger than 1000 µm 15%.

As of this writing, March 22, I have not tested with emmer. Emmer has a sweet and nutty taste. Thinking in terms of agency, perhaps emmer was selected purposefully for this bread to go with the imported celery seeds. One would want the best for a bread with an expensive ingredient, so I think we can imagine the emmer/wheat mix as being deemed “best.” I think that the right mix and the right hydration can be worked out buy focusing on the round stamp in the center of the bread. You want a shallow crisp indent. The flour that allows for that is the flour mix to use.

Milling: See Appendix.

Celery seeds: Add celery seeds to the dough to taste.

Salt: Option, but likely given that this is a luxury bread.

Forming the loaf. Pat approximately 110 g of dough into a disk 110 mm in diameter and 20 mm high. After patting into a disk, make a circular stamp in the middle, as per the sample. The fact that that stamp has a crisp edge, and is close to the surface, probably holds the key to both dough hydration and the emmer/aestivum grain ratio.

You cannot get such a crisp stamp from 100% common wheat flour, especially if you knead the dough. Grains were grown as mono crops, as now. There were breads made with 100% common wheat flour doing the Neolithic, so if you can’t get emmer, then make the bread anyway.

Baking: Bake in an oven at a moderate temperature until done.

Appendix:

Milling the barley.

Flour specifications: 29% white (<300 Microns), 25% semolina (between 300 and 1000 microns), 35% grist (between 1000 and 56000 microns).

The barely that you want to use, the one that will produce the most authentic result, still has its bran coat, but is often hard to source locally. Pearl barley, that lacks bran, is the most common barely sold.

If you can’t mill your own with a flour mill, then use a spinning blade coffee mill and be extemporaneous. Semolina is granular like pasta or shoji flour. Grist is like bulgar. Buy barley flour form the 29% that is fine flour.

To mill and sift then use screens as follows:

Use a 300 micron screen, a 1000 micron screen and a 2000 micron screen.

(1) Sift your meal through the 300 micron sieve. That yields white flour.

(2) Re-sift what is held back through a 1000 micron screen. What passes through that sieve is the Heiss “semolina” category.

(3) Sift what was left in the 1000 micron screen through a 2000 micron screen. What is held back in that screen is not used in the bread.

The bread included whole barely seeds, so add some barley seeds to the dough. Whether they were soaked first, we do not know.

Milling the Wheat

If you are using a whirling-blade coffee grinder then start with 43% of your flour weight being white flour from the store, ideally, a mix of emmer and bread wheat. Grind grain to what looks right for the 24% semolina and the 15% grist fractions.

If milling with a flour mill, then adjust your grinder to get a mix of particle sizes. On my mill, I can adjust as the mill is running.

Starting with your mixed meal, sift that through your 300 µm sieve to get the 43% of the particles are less than 300 µm. What is held back by that sieve you next run through the 1000 µm sieve. What falls through that is your semolina. Lastly, run what is held back by that sieve through a 2000 µm sieve. That gives you your grist. Mix the three fractions in the ratio of 43% fine flour, 24% semolina, and 15% grist.