Note: Links to Koujun Tsunoda’s paper, Allan Phipps’ paper, and Tsunematsu Tokemoto’s patent application for an ibotenic acid flavoring are listed at the end of this review. I also link to Heikki Pyysalo’s paper on Gyromitra esculenta detoxification. This brings together all of the important papers on the detoxification of mushrooms with water-soluble toxins. Basic links are also included to Fick’s laws of diffusion, essential for understanding how detoxification works. Please familiarize yourself with the diffusion concept before delving into this text and the referenced papers.

Koujun Tsunoda’s paper, “Change in Ibotenic Acid and Muscimol Contents in Amanita Muscaria During Drying, Storing or Cooking,” is the definitive work on the detoxification of Amanita muscaria. The two compounds in this mushroom that are potential problems for consumption are ibotenic acid (C₅H₆N₂O) and muscimol (C₄H₆N₂O₂). Both are psychoactive in low doses. Based on anecdotal information, the published lowest observed adverse effect level (LOAEL) is in the range of 30g to 50g of fresh material, which works out to between 0.42 mg/kg and 0.71 mg/kg. As dose is always the fundamental concept underpinning consumption of drugs and toxins, to calculate the effects of eating a given quantity of A. muscaria, you multiply the amount of mushroom you want to eat by the concentration of ibotenic acid and/or muscimol in the mushroom to arrive at the total.

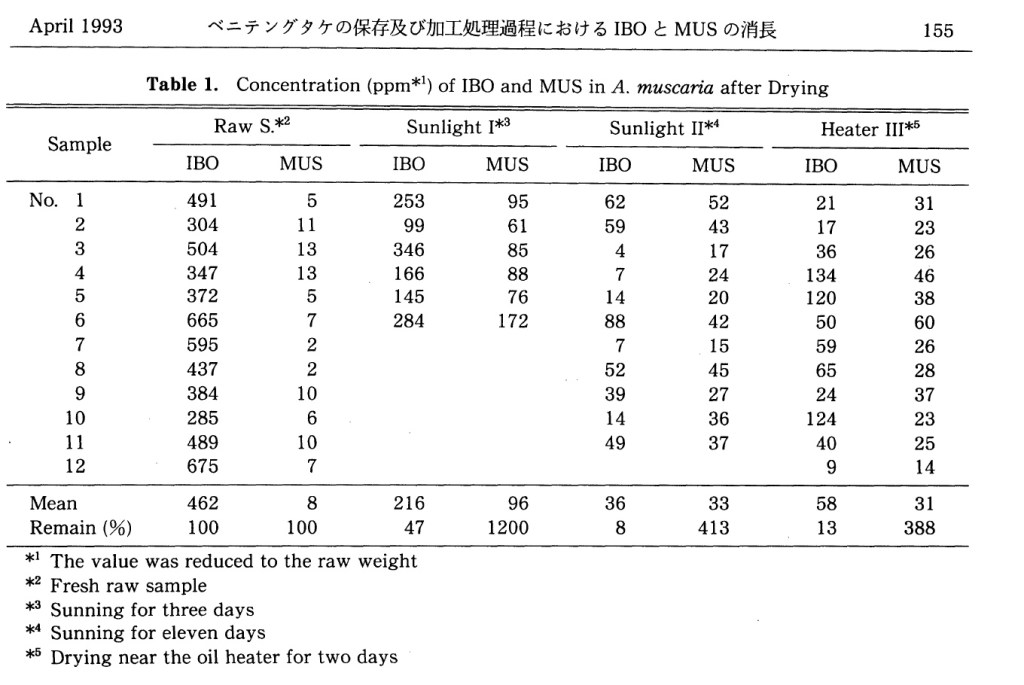

Toxicity varies mushroom to mushroom, as you can see from Table 1 in Tsunoda’s study (below). The calculated mean for this study was 462 ppm or micrograms/g of substrates. This is what you get when you homogenize the samples, while any given mushroom might have a greater or lesser concentration. If you are interested in ingesting the mushroom for its inebriating effects, then you will want to convert as much ibotenic acid to muscimol as you can, while still obtaining psychotic benefits without as many negative side effects, such as nausea.

Tsunoda and his colleagues were looking at how the traditional processing systems of the mountain people of Nagano Prefecture affected levels of ibotenic acid and muscimol. As there were traditional uses as a social inebriant and as a comestible, the paper covers the effect of different processing systems — mainly drying and boiling — on levels of ibotenic acid and muscimol.

Alan Phipps (2002), working roughly ten years after Tsunoda, also documented consumption as an inebriant and as a comestible — a muscaria pickle. Phipps’ equipment was not as sensitive as Tsunoda’s, so his work does not exactly replicate Tsunoda’s. But Phipps does demonstrates the central concept that certain processes, such as drying, increase muscimol relative to ibotenic acid. Boiling, Phipps found, quickly allows the toxins to diffuse into water, where they can be thrown away, leaving behind a tasty edible mushroom.

In Table 1 (below), Tsunoda shows us the range concentrations of Ibotenic acid (IBO) and its derivative muscimol (MUS) in fresh material (columns 2 and 3), and again after drying as per various local drying traditions (columns 4 through 9).

Table 1 offers three takeaways.

(1) Raw material contains mostly ibotenic acid. In its raw state, the concentration of muscimol is not significant. In its raw state, the quantity of ibotenic acid is highly variable.

(2) After three days in the sun (columns 4 and 5, “Sunlight I*3”), we see a significant drop in ibotenic acid, and an even more significant increase in muscimol. In the line for Sample No. 1, ibotenic acid decreases 50%, from 491 ppm to 253 ppm. Some of that was converted into muscimol, which increased roughly twenty times, from 5 ppm to 95 ppm.

(3) The decline in ibotenic acid is not 100% attributable to its decay into muscimol. Other detoxification processes are at work, though not explained in the paper; it does mention that the processes are not purely stoichiometric. We can see from the table, however, that both ibotenic acid and muscimol are degraded by heat as we approach 120C. That temperature, however, is too high to be used as a detoxifying technique, because the texture and nutritional value of the mushrooms will degrade at that temperature.

(4) The 11-day dry in sunlight (columns 6 and 7, “Sunlight II*4”) shows that the mushroom is now edible in measured quantities. Multiply any of the paired numbers of IBO and MUS by the grams in your hypothetical serving and divide by 1000 to find the milligrams of IBO and MUS in the serving, and compare with the current working numbers for LOAEL (lowest observed adverse effect level) dose of 30g for ibotenic acid and 6 mg for muscimol.

(5) As the toxins are water soluble, a cook who starts with mushrooms dried for 11 days begins with a product that is edible in side-dish quantities, and will be even more toxin-free after parboiling or parsoaking for 5 to 10 minutes.

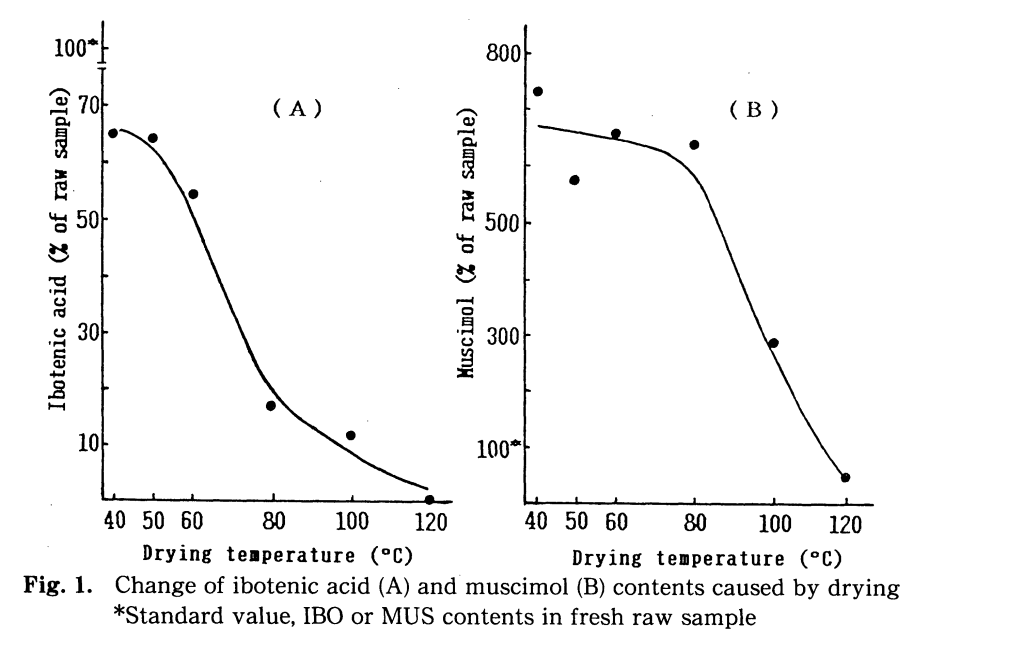

Ibotenic Acid and Muscimol are Both Thermolabile

In Figure 1 (below), one sees that both ibotenic acid and muscimol are affected by heat. They are thermolabile. It seems that they rapidly degrade at about 120C. Unfortunately, 120C is too high a temperature to be of value for culinary purposes. At this temperature, one begins to damage the nutritional qualities of the dried specimen, and to alter its texture upon dehydration. It is best not to dry mushrooms above 55C.

Grilling for Taste, Not for a High

Phipps (2002) reported that men consumed fresh grilled mushrooms in restaurants, suggesting use as an inebriant. However, the men Phipps spoke with told him they did not eat the mushrooms to get inebriated but for taste. We might take this in with a smirk, but I think, the subject country being Japan, we should take consumption for taste at face value.

Japanese cuisine is often built around subtleties of taste and texture. Japanese cuisine often highlights a single ingredient, which may be presented on a plate just for it. The Japanese also celebrate seasonal flavors — even if that means strawberry sandwiches at Family Mart and 7-11.

Might a 15g piece of mushroom containing between 5 and 10 mg of ibotenic acid be that kind of taste? Yes, it could. It could be just such a special taste — an aki no mikaku (秋の味覇), a special taste of autumn.

Referencing Table 1, even the most toxic of the fresh samples — the one with 665 ppm ibotenic acid — only contains 10 mg in a 15g raw serving. This would be roughly one third of the 30mg lowest published threshold dose. That is because ibotenic acid is both a taste enhancer, like MSG, but also has its own flavor.

The Lingering Sweet Taste of Ibotenic Acid

“Tricholomic acid and ibotenic acid have respectively a mild, subtle, delicate taste and a good body, and the taste is a lingering one, i.e., persists for a long time. Further, the threshold values of these compounds are far lower (about that of monosodium glutamate).” From U.S. patent application US3466175A by Tsunematsu Takemoto, 1964.

Tsunoda undertook his study because people were eating the mushroom. Why are people eating a mushroom with a reputation for toxicity as an esculent? The answer is, ibotenic acid gives it a special taste. As we see from Tsunoda’s tables and figures, there is always some residual ibotenic acid even after the levels of toxicity are reduced far enough below threshold doses to make eating it safe. This also means it always has an edge — a lingering sweet taste and a general enchanted sense of umami.

Ibotenic acid is an analog for MSG. It is also many times a more powerful flavor enhancer than MSG. And, it has its own pleasant, if subtle, taste. Grilling a small amount of fresh material will give you a strong hit of a delicious taste that, like a sweet kiss, lingers.

The 1964 Tsunematsu Takemoto U.S. patent application for a flavor enhancer employing ibotenic acid is likely based on the understanding that, as Phipps (2002) documents, powdered dried A. muscaria was used by some as a flavoring agent. Here is how Takemoto explains ibotenic acid’s power as a flavoring agent.

“The threshold values of tricholomic acid and ibotenic acid are estimated to be about 0.003% which is far lower than that of monosodium glutamate, 0.02%. Further, as mentioned herein before, when tricholomic acid or ibotenic acid is employed in combination with 5′-nucleotide, a remarkable synergy is observed between the tricholomic acid or ibotenic acid and the 5′-nucleotide. Therefore, tricholomic acid or ibotenic acid used in this way is effective in an amount below its threshold value, and the seasoning effect is perceptible at the level of about one-tenth of the threshold value. “

In other words, when you consume ibotenic acid along with umami rich foods, you improve the taste of everything. Ibotenic acid triggers good things happening in our mouths when we take it in along with other mushrooms, meat, shellfish, or legumes.

Slight Digression: Ibotenic Acid is the Focus, Not the Mushroom Species it Comes From

Although it is a digression, it is worth reminding readers that ibotenic acid is not linked to any one mushroom species. Fick’s laws of diffusion (explaining how water solute detoxification works) is also a process that is not linked to any one mushroom species. Takemoto’s patent is about two compounds — tricholomic acid and ibotenic acid. All mushrooms containing these compounds are prime edibles, because in all of them the residual ibotenic acid is enough to render them both flavor enhancers, and mushrooms with a sweet lingering taste in their own right.

Tsunoda’s 1993 study concerning A. muscaria could have been conducted with any other ibotenic acid-containing mushrooms. Fick’s laws of diffusion work the same in all fleshy fungi. The toxic compounds will always flow from areas of high concentration to areas of low concentration. Tsunoda had to use A. muscaria because his was an ethnographic study, but he would have had the same results had he used A. strobiliformis, or some other ibotenic acid-containing Amanita.

PH Matters

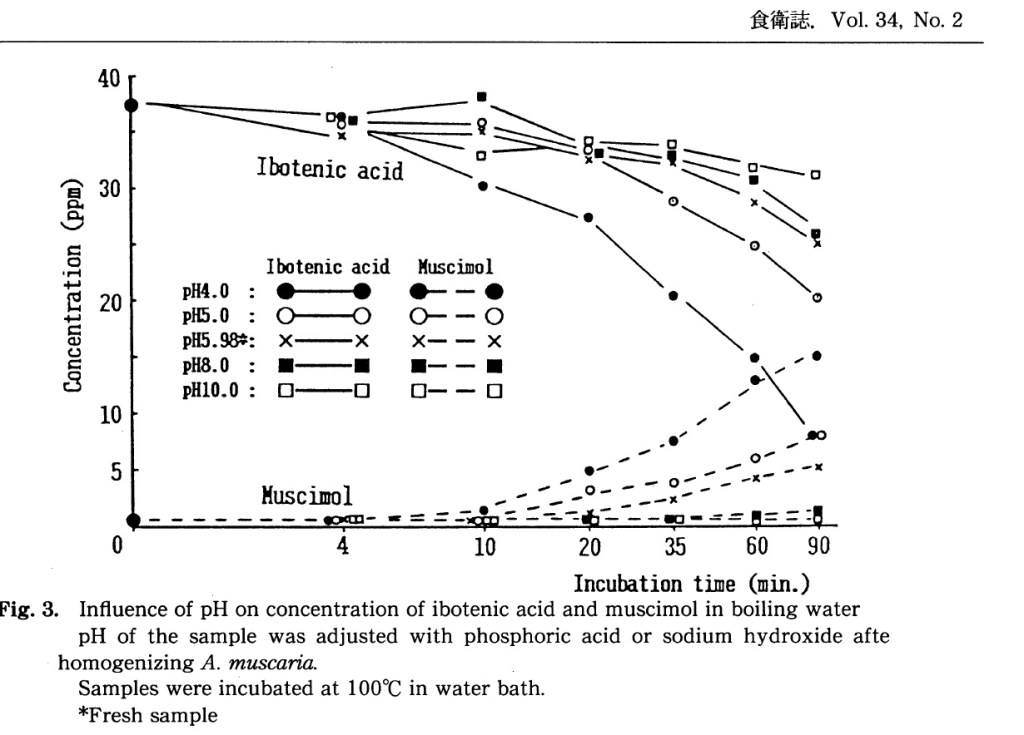

Figure 3 (above) concerns how PH affects the detoxification of ibotenic acid and muscimol. When the solute is basic — PH 10 — the diffusion of ibotenic acid slows down and its conversion into muscimol is accelerated. The takeaway for the home cook is to use water that is neutral; for example, tap water in my community is PH 7.4. As diffusion into water is so efficient, there is no practical need to diffuse into acidified water.

Figure 3’s importance is to illustrate the power of cold-water diffusion. Note that all samples begin with the concentration of approximately 38 ppm. This is because we are starting from a homogenized sample which, from Table 1, we know begins with a concentration of 462 ppm, or 462 micrograms/g. A 50g serving of the mushroom (½ cup) would have 1.5mg of ibotenic acid. We are working from 30mg being the quantity that triggers the lowest observable symptoms. What we are looking at here is really the long tail of a detoxification process that took place with ice water.

Here is how the samples were prepared for Figure 3. For the drying experiment, the caps were left whole and the stems cut in half lengthwise. No trimming is mentioned prior to boiling. My personal experience in Ueda, Japan, in 2019 was that the mushrooms are boiled whole. This has big implications for diffusion, as diffusion is facilitated through smaller slices of mushroom. Geometry — the size of pieces — is a key datapoint when using Fick’s diffusion equations. This study is of folk practice. It is not a study designed to maximize the mushroom detoxification. As one sees in this photograph (below) I took in Ueda, Japan, along with mycologist David Arora, the Japanese like to work with whole mushrooms.

“冷蔵生試料各 100 g (7回)に氷水5倍量を加え,ホモジナイザーで均質化した後,リン酸及び水酸化ナトリゥムで pH 4.0, 5.0, 5.98, 7.0, 8.0, 9.0, 10.0 のそれぞれに調整した。その試料溶液を沸騰浴中で加熱した。”

“100 g of refrigerated fresh samples (7 times) were added to 5 times the amount of ice water, homogenized, and then adjusted to pH 4.0, 5.0, 5.98, 7.0, 8.0, 9.0, and 10.0 respectively with phosphoric acid and sodium hydroxide. The sample solutions were heated in a boiling water bath.”

My sense is that Tsunoda assumed all readers would have taken for granted that if no soaking time was mentioned, it had to be something simple and common — a timing “everyone” knew, like 12 or 24 hours. A patent application that cites the Tsunoda paper diffuses mushrooms in 42F water for 24 hours, so, let’s take that as a likely time period.

Replication Experiment

Replicating the experiment would clarify that timing. Replication would also make it possible to note how quickly the toxin flows into water after 5 and 10 minutes through multiple changes of water. As each water refreshment resets the diffusion gradient, a great deal of detoxification ought to be accomplished in a short time. Working with cool water is easier than working with boiling water. It is also easier to be sure there is at least a 5:1, preferably a 10:1, dilution ratio. You can’t have too much water! When replicating the experiment, pay attention to mushroom geometry. I suggest testing for whole mushrooms, as well as slices ranging from 4 mm to 8 mm.

Soak First, Then Boil?

In Japan, I observed that the mushrooms are always boiled for making pickles before soaking, and the bitterest forms of cassava (Manihot esculenta) are soaked for a couple of days prior to boiling! A long soak in the refrigerator with several changes of water might suffice to detoxify the mushroom sufficiently to eat it, or to act as a pre-detoxification process before boiling.

Agitating the water in cool-water experiments is always a good idea. In boiling water, the convection currents make stirring unnecessary.

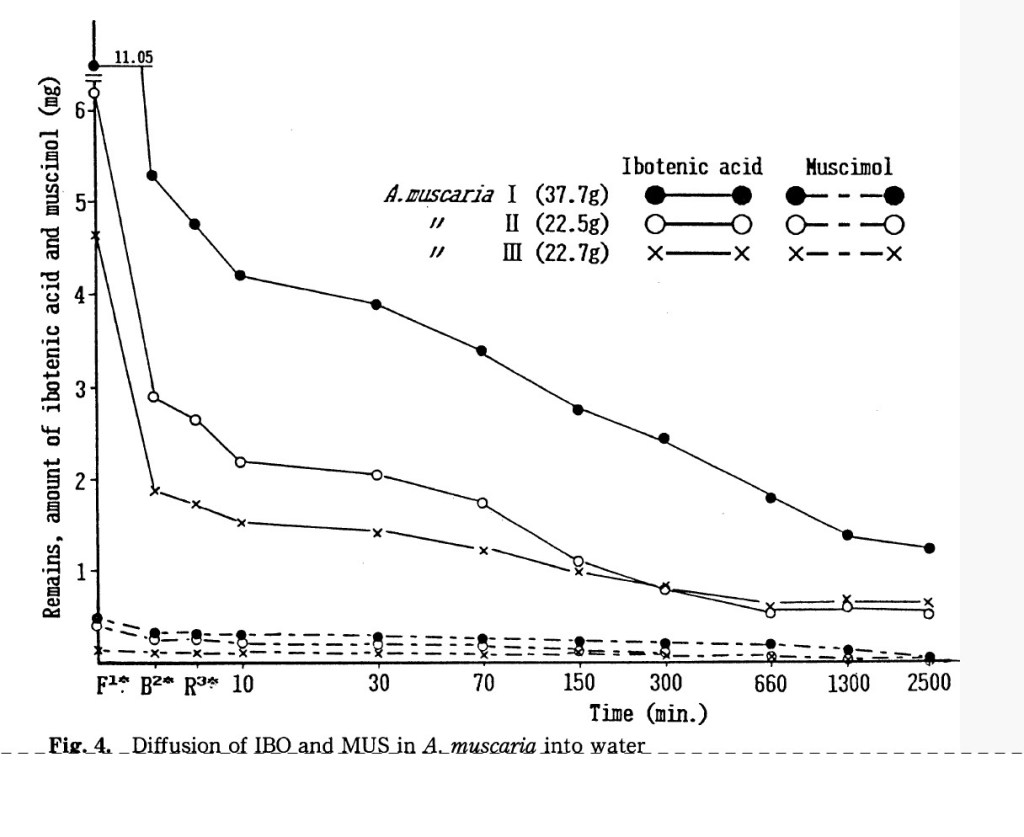

Figure 4 (below) is a clean test of the 10-minute boil, and also offers insights into detoxification in room-temperature water. Note: the X axis scale is not linear!

In Figure 4 you see three different A. muscaria samples that have each been boiled for 10 minutes. The sample is not homogenized. The starting concentrations of the raw material are not given. The starting concentrations after their 10-minute boil, converted from milligrams to parts per million (we are given the starting concentration on the y axis, and the size of the samples, which enables us to calculate the parts per million), are as follows for Samples I, II, and III: 293 ppm, 278 ppm, and 209 ppm. Results for I and II are roughly the same. Geometry is important in Fickean systems. My speculation is that Sample III may have been enough of a physically smaller specimen in terms of stalk diameter or cap size to have facilitated much faster diffusion.

But, what I want you to focus on in Figure 4 — what matters the most —is to recognize that we have initial declines that are exponential. AFTER the specimens already lost roughly half of their toxicity in the first 10-minute boil (compare ending ppm with raw concentrations in Table 1), the 10-minute decline in room-temperature water clusters between 59% and 64%.

The concentrations at the 10-minute mark cluster around 100 ppm for the first two experiments and are around 55 ppm for the third specimen, the one we speculate whose pieces are much smaller than the first two. If one were to cook up the mushrooms at this point, then could you safely eat a reasonably sized side dish? Yes, you could. A 50g (½ cup) serving at 100 ppm contains 5mg ibotenic acid. This is 6 times less than the 30g threshold dose.

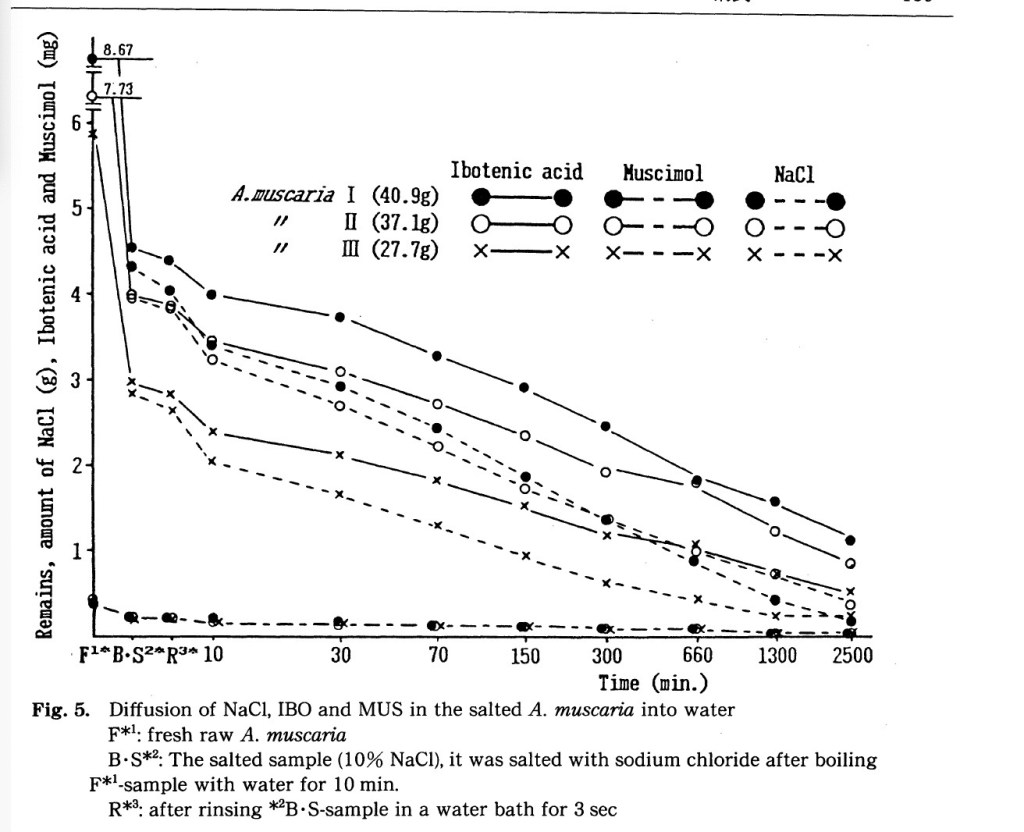

Figure 5 (below), the last figure in the study, concerns the salting aspect of Japanese traditional culinary practice with A. muscaria. For the larger purpose of understanding the detoxification of mushrooms with water-soluble toxins, I suggest just focusing once again on the steep decline in the first 5 to 10 minutes, illustrating (again) the power of refreshing the concentration gradient, as per best practices explained by Fick’s laws of diffusion. The three samples had, as in Figure 4, been boiled whole. Initial concentrations were not noted. The scale is not linear. Refreshing the water a few times after 5 minutes would have achieved the same results in less time.

Ficks Laws: Refreshing the Concentration Gradient is What Makes Diffusion Happen

Fick’s laws of diffusion describe the force that drives diffusive systems. That force is the concentration gradient — the difference between the concentration of the toxin in the mushroom and the concentration in the water into which the mushroom is immersed. You reset the system every time you refresh the gradient by changing the water. While the system does slow down as the concentration in the substrate approaches zero, you get quite a few strong punches upon refresh, as the current studies show. For mild toxins like ibotenic acid, one or two boils, or one or two soaks, can be sufficient to render the mushroom edible — and, I will say, amazingly, even when the mushroom is left whole!

Papers Mentioned

The following study by Heikki Pyysalo and Aimo Niskanen concerns the detoxification of Gyromitra esculenta. It was commissioned by the Finnish government and performed in a government lab. This study is the basis for the Finnish government’s protocol of two 5-minute boils in 3:1 (water to mushroom) as the way to safely detoxify G. esculenta. As you will see, the experiments have a great deal in common with those of Tsunoda. A double 5-minute boiling protocol is likey effective for A. muscaria if the mushrooms are first cut into slices.

Notes:

** Phipps numbers are not credible. No other study has as high concentrations of ibotenic acid or muscimol as his does. Nor does any study have as low concentrations of ibotenic acid at the 10-minute boil point that he does. Thus, use his graphs as concepts rather than as offering citable datapoints. When you convert his mmol/kg to ppm you will see the problem. The molecular weight of muscimol is 114 g/mol and that of ibotenic acid is 156 g/mol, which you will need to convert his data to ppm and on the low end, his equipment is not sensitive enough for all of the experiments he undertakes.