This page provides the recipe and mise en place information for participants in my Thursday Seminar/Workshop #9 on English French Bread. If you are registered for the Seminar I suggest you also register at my Facebook group: Bread History and Practice. That is where participants post images of their breads and we continue the discussion started in the Seminar.

The lightly enriched yeasted bread favored by the French elites defined what people outside of France thought of when one said, “French bread.” The bread that we will be making on July 9 was the type of bread people thought of as “French bread” in the 17th century through at least the first half of the 19th century. It was always made with the best white flour, was always yeasted, and was always enriched with milk, at least, but often also with some butter and eggs. French bread was never as enriched as a brioche, but was never just flour, water, leavening, and salt. The dough for “French bread” was the same as that used in “French rolls.”

The, to us, curious aspect of English French bread and rolls is that it was always (or at least almost always) rasped or chipped before serving. It was thus baked in a hot oven so that a crisp crust is formed. This is in complete contrast with the manchet which was cooked in a slow oven and came out with a pale crust. Chipping or rasping bread is its own story, and it deserves a separate talk, but I would be remiss not to suggest that you have a rasp handy for this bread, or, lacking a rasp, a knife you can use to chip off the crust. While most recipes specify rasping, (as it happens the one we are using does not), there were critics of the rasp on the grounds that it made the final bread or roll too smooth. These critics preferred chipping with the knife, so, if you don’t have a rasp, don’t worry, this puts you in the camp of E. Smith, the first successful female cookbook author who first published in the 1740s.

Here is the text of the original recipe.

English French Bread – 1708

“Take one quart of Flour, three eggs, a little Barm, and a little Butter; mix them with the Flour very light with a little new Milk warmed; then lay it by the Fire to rise; then make it into little Loaves; flour it very well, and bake it in a quick Oven.” Henry Howard, England’s Newest way in all sorts of Cookery (1708)

Note on this redaction. For most of the ingredients Howard is big on the term “little.” He calls for a “little” barm, milk, and butter. This said, Howard is precise where we need him to be — the flour and the eggs — and leaves the rest up to his period readers with whom he had a shared understanding that this bread was made with a relatively soft dough — at least compared to the manchet. My redaction is for a 73% hydration. That puts into the low end of what we use today in our modern, unenriched “French bread.”

Salt: This recipe does not mention salt. As a rule, I don’t like assuming errors in recipes whenever one finds something one doesn’t expect. In this case, I am pretty certain that most, if not all other French bread recipes include salt. About fifteen years ago I encountered a bread that is pretty much identical to this one in Mexico that was made without salt — the man who gave me the recipe emphasized “sin sal.” I often make this recipe without salt, as written, and enjoy it as toast, with cheese, and with soup, which is how it was often used. If you do want to add salt, then add up 2% salt – my advice is around 7-8g salt, but you can go up to 10g.

Hydration: I have interpreted the recipe to end up with a hydration of around 73%. This seems to be where the dough stops being stiff and becomes soft. Period diners would have recognized the crumb as different from manchet, which was made with a much stiffer dough. As always, adjust the water as needed because your flour and my flour may absorb different amounts of water. I live in a relatively humid climate, and you may not.

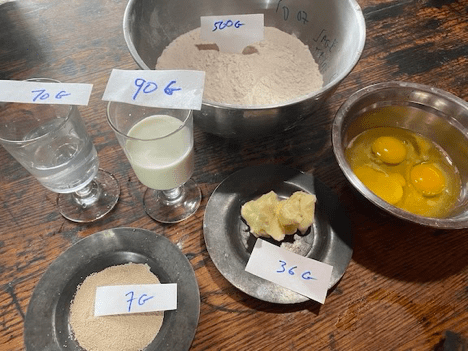

Baker’s Math

100% unbleached all-purpose flour

41% egg (preferably from backyard chickens)

7% unsalted soft butter broken into small pieces

18% warm milk, preferably raw

14% warm water

1.5% dried yeast

Salt to taste, 1% to 2% (not in original recipe, but salt is in other French bread recipes)

Weights for 1 quart white flour

500 g unbleached all-purpose flour

3 eggs, preferably from backyard chickens

35 g unsalted butter broken into small pieces

90 g warm milk, preferably raw

*70g warm water

*7g dried yeast

5g – 10g salt (not in original recipe, but salt is in other French bread recipes.)

*Note: If you have access to barm, then use 70g barm rather than 70g water plus dried yeast.

Equipment:

2 bowls

Electric mixers or whisk

1 baking tin, buttered (optional)

Method:

1. Put flour in a bowl. If using dried yeast, add it to the flour.

2. Beat the eggs in a separate bowl.

3. If using dried yeast, warm the combined milk and water. If using barm, then only warm the milk.

4. Whisk up the soft pieces of butter in the warmed liquid until the butter is broken up into very small pieces. Then add to the egg mixture and whisk for a few strokes. If using barm, then add it here.

5. Pour the liquid ingredients into the flour. Mix until mostly incorporated. Period bakers would have used their hands. Complete the mixing by turning out onto a work surface, and gently kneading a few times until flour is fully combined.

6. Cover, and set aside in a warm place, (38C (100F). This will replicate warming by the fire. When doubled, turn onto a floured board, and gently de-gas. Continuing to handle the dough gently and, dusting with flour as necessary, form into between 4 and 7 rolls or optionally as a loaf. If using a loaf pan, then butter it. While period recipes did not specify proofing periods for formed loaves, my advice for this recipe is to be sure you let the dough rise until nearly double before baking.

7. If making the roll form, then bake in a wood-fired bread oven before the main loaves go in, otherwise bake after the oven has cooled some. In a kitchen oven preheated to 190C (375F). Bake for ten minutes and then lower the oven to 180C (350C). Note that baking times are influenced by the shape of the loaf tin and the size of the rolls. Loaves will bake in approximately 40 to 50 minutes. I have not tested rolls. I’d estimate 10 to 15 minutes.